^McCoy Wash sunset.

Confessions of a Tortoise Biologist

April 30, 2010 - By Laura Cunningham

Back in the days when I worked as a private contracting tortoise biologist (I no longer do), we happened to survey for tortoises on McCoy Wash near Blythe in Riverside County, California. Today it is the site of one of the largest solar thermal power plant proposals in the Southwest, the Blythe Solar Power Project by Solar Millennium.

A group of us carried out a "Presence-Absence Survey" for Desert tortoises (Gopherus agassizii) on May 9, 10, and 11, 2000. Back then the project was a flood-control dam on the northwestern edge of Blythe that would affect both public land and private farms. It never happened, but in the desert nothing is ever really safe from development.

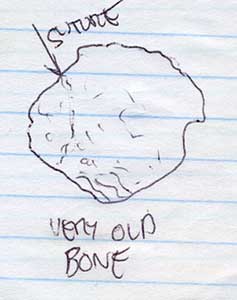

We found a lot of tortoise sign on the higher flats, as well as burrow and a big female on the eastern side. We surveyed part of the Blythe Solar project area which lies on the western side of the main wash, and found tortoise bones, old scutes. The entire area appeared to be good habitat, despite the possibility that a die-off occurred at some point in the past, perhaps due to drought. But nothing would prevent tortoises from increasing in this area if conditions allow.

^Tortoise shell bone, from my field notes.

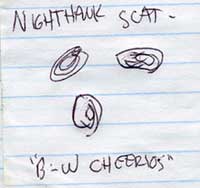

The surveys we did could not estimate abundance of tortoises. Other survey methods must be used to do this. The days were long, 10 and 11 hours, as we walked parallel to each other across the desert pavement, through Ironwood thickets, and over creosote flats. The temperature reached 100 degrees Fahrenheit at 2 PM. Wildlife was abundant, many lizards and snakes, and spring migrant birds. Sign of mammals was common as we kept our eyes to the ground looking for tortoises and their burrows, tracks, scat, and any carcasses.

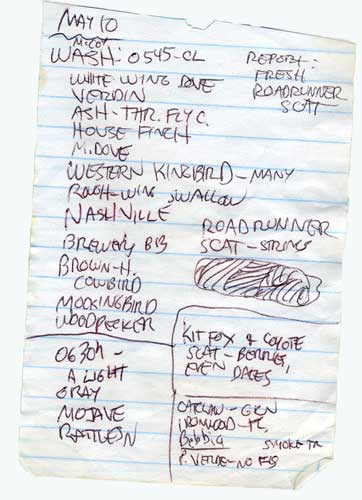

The place was beautiful and full of life. I always take field notes of what I see, and following is a snapshot of McCoy Wash natural history.

^Field notes.

^Surveyors take a break in McCoy Wash.

Reptiles Abundant

Zebra-tailed lizards (Callisaurus draconoides) skittered across sandy washes all day. Tan-colored Desert horned lizards (Phrynosoma platyrhinos) hunted harvester ants. Large Leopard lizards (Gambelia wislizenii) hunted other lizards like carnivorous dinosaurs. Little Side-blotched lizards (Uta stansburiana) were especially watchful of these predators. Western whiptails (Cnemidophorus tigris) actively hunted insects and dug in leaf litter for desert termites. Large Desert spiny lizards (Sceloporus magister) climbed up Ironwood trunks.

^A light-gray Mojave Rattlesnake (Crotalus scutulatus) curled up under a shrub in the morning.

A Western patch-nosed snake (Salvadora hexalepis) moved about on desert pavement one morning, then raced under a large Desert straw bush (Stephanomeria sp.).

Mammals and Sign

Antelope ground squirrels (Ammospermophilus leucurus) ran about in the heat of day, and an occasional Round-tailed ground squirrel (Xerospermophilus tereticaudus) peeped from its burrow.

Kangaroo rat (Dipodomys sp.) burrows occurred everywhere. Their burrow mounds broke the natural desert pavement in small areas, allowing small wildflowers to grow on loose soil.

Coyote (Canis latrans) scat indicated the desert dogs were eating Lycium berries, and even dried dates from Blythe. Kit fox (Canis macrotis) sign was even more common.

Black-tailed jackrabbit (Lepus californicus) scat gave clues to its diet: the rabbits were gnawing on Palo verde (Cercidium microphyllum) twigs, the first trees to leaf out here.

^Ironwood trees (Olneya tesota) groves in McCoy Wash area.

Varied Colorado Desert

To the west of the large McCoy Wash mainstem, stony desert pavement stretched far on the flatlands, divided by smaller washes and gullies full of Palo verde (Cercidium microphyllum -- named "green stick" for its photosynthesizing twigs, and purple-flowering Ironwood trees (Olneya tesota). The valley is framed by the McCoy Mountains and Big Maria Mountains and drains into the Colorado River to the east.

Creosote (Larrea tridentata) and Bursage (Ambrosia dumosa) are common, with Big galleta grass (Pleuraphis rigida) filling some gullies, still dry waiting for summer rains.

Catclaw acacia (Acacia greggii) were greened up, Smoke trees (Psorothamnus spinosus), Cheesebush (Hymenoclea salsola), tall Wolfberry bushes (Lycium sp.), and Chuckwalla's delight shrubs (Bebbia juncea) grew in washes. A few Honey mesquites (Prosopis glandulosa) also grew in washes.

Other plants included Desert milkweed (Asclepias erosa),

Climbing milkweed (Sarcostemma hirtellum), Brittlebush (Encelia farinosa), Spiny chorizanthe (Chorizanthe rigida), and Rattany (Krameria sp.).

A Devil's claw pod (Proboscidea althaeifolia) littered the ground. Bottlecleaner evening primrose (Camissonia boothi) remnants could also be found. We also saw a few Ocotillos (Fouquieria splendens) scattered.

Pencil chollas (Cylindropuntia ramosissima) and Silver chollas (C. echinocarpa) dotted the landscape.

An annual Three-awn grass (Aristida sp.), plantain (Plantago ovata) already dried in the heat, and low fuzzy Daleas (Dalea mollis) grew on the desert.

^Tree groves of Palo verde, Ironwood, and Catclaw acacia.

^Ironwood with leaves and flowers, as well as dark green mistletoe.

If the Blythe Solar Power Project is approved, a different type of tortoise survey will be done: a "Clearance Survey." The area will be fenced off in phases and numerous "biologists" will try to remove all tortoises from the area, in this case the 7,000-acre disturbance area. After tortoises are removed from burrows in one sweep, a second sweep will require shovels. All burrows will be dug out, all tortoise burrows, Coyote dens, Kit fox burrows, ground squirrel buurows, down to the smallest kangaroo rat burrows (because juvenile tortoise may shelter in them). Shrubs will be pulled apart to make sure tortoises are not hiding in dense vegetation. Burrowing owls will lose their homes.

Tortoises will be relocated to another area approved by the US Fish and Wildlife Service. But during recent Fort Irwin expansion relocation and translocation efforts, more than 40% of tortoises died because of this. Coyotes often found the relocated tortoises, stress may have caused the death of others. Impacts happen to resident tortoises already living in the relocation areas. Then there is the question of spreading diseases among populations.

Obviously moving tortoises is not a viable way to "recover" this Federally Threatened species.