Wildlands Conservancy Tries to Protect Desert Along Historic Highway

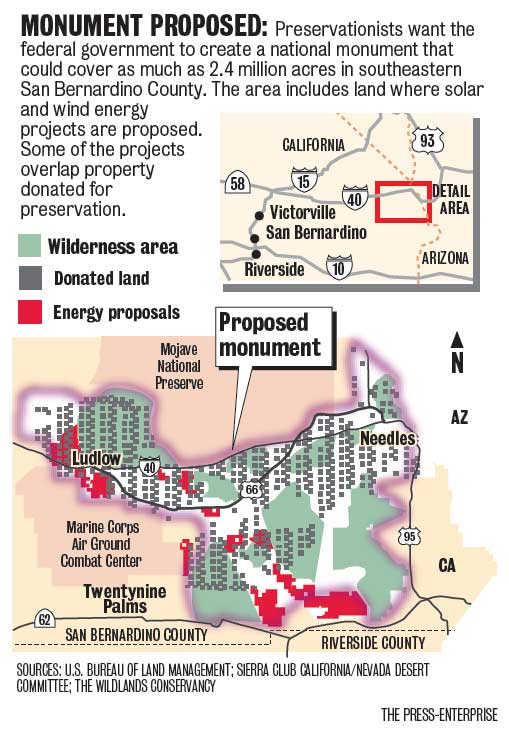

UPDATE: December 21, 2009 - Senator Feinstein (D-CA) introduced bill to make "Mojave Trails National Monument">>here.

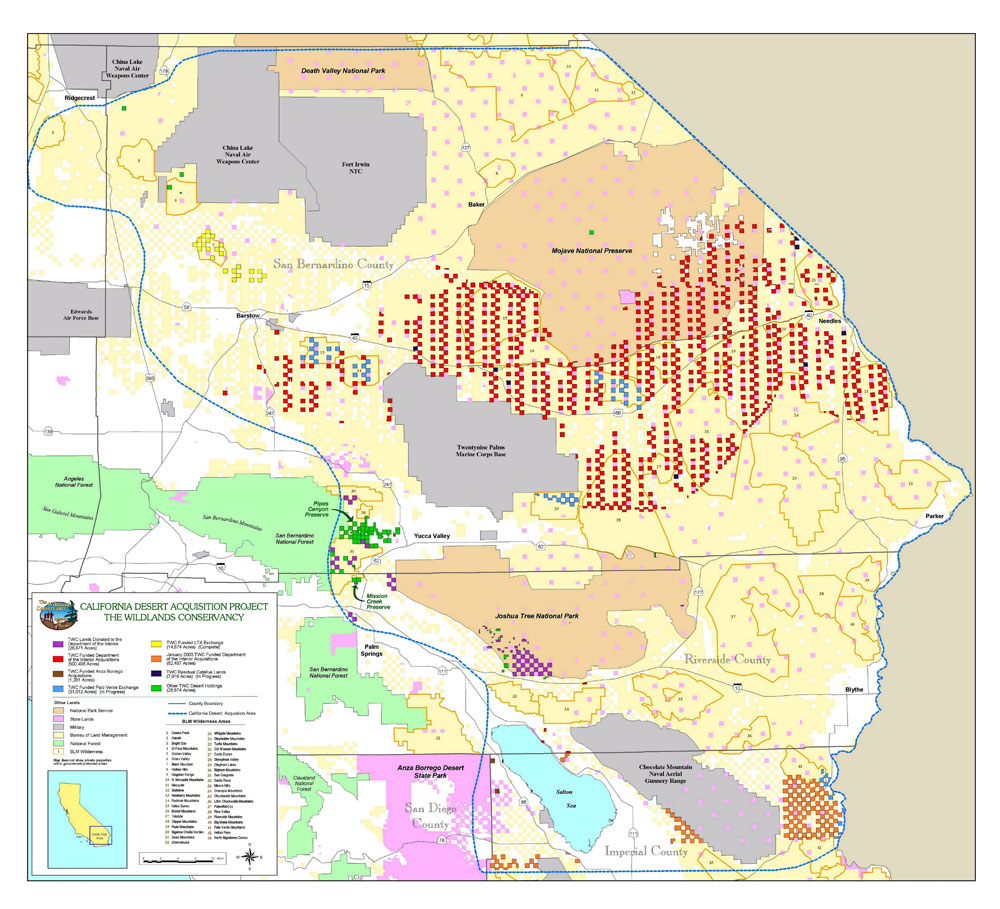

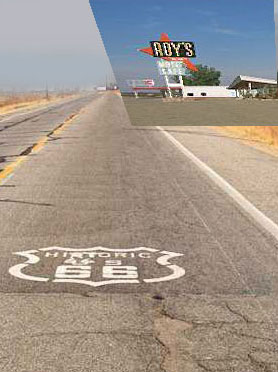

Preservationists seeing the future of military expansion and renewable energy development in the California desert are creating a plan to create a large national monument east of Barstow and Twentynine Palms to Needles along the Colorado River, while protecting 70 miles of historic Route 66. The Wildlands Conservancy, based in Oak Glen, California, raised about $45 million to buy Mojave Desert land from the Catellus Development Corp., a former branch of the Santa Fe Railway. They purchased nearly 600,000 acres of scattered desert and donated it to the federal government as open space, specifically to the Bureau of Land Management (BLM). The emerging non-profit Route 66 Alliance proposes calling it Mother Road National Monument, a phrase coined by John Steinbeck in The Grapes of Wrath where Oklahoma dust bowl families use it to access the promised land of California. Route 66 was officially decommissioned in 1985 and replaced with larger Interstate highways.

^The strange black lava flow of Pisgah.

The desert views along the old and sometimes crumbling highway are awe-inspiring and diverse, from black lava flows, sand dunes, and cinder cones to jagged ranges such as the Bristol, Old Woman and Turtle Mountains, and broad basins like Cadiz and Ward Valley. Mojave creosote scrub graces the western areas, grading into Colorado Desert southeastward. Icon road stops like Bagdad, Siberia, Amboy, and Goffs with its train depot are strung along the road like distant oases.

But the land is also "some of the most valuable for solar development on earth," BLM district manager Steve Borchard said recently. He explained that BLM did not commit to preserving land donated by The Wildlands Conservancy. BLM is considering 162 applications for large-scale solar and wind projects on more than a million acres in its California Desert District.

When the conservancy-government land deal concluded in 2004, no one saw the renewable energy land rush coming.

^Cadiz Valley with Smoke trees (Psorothamnus spinosus).

The land transfer was the largest of its kind in state history. It involved 160 one-acre parcels laid out like a checkerboard along either side of the railroad tracks from Barstow to the Colorado River, the result of a grant from the government in the 1800s to spur development. The conservancy's purchase tapped $18 million from the federal Land and Water Conservation Fund, intended to preserve and develop access to outdoor recreation areas.

Desert conservationists don not oppose renewable energy, but prefer rooftop solar units, or larger projects on land that already has been disturbed, such as abandoned farms (see The Solution).

Various checkered land acquisitions of The Wildlands Conservancy: red is land along old Route 66. Courtesy The Wildlands Conservancy.

Courtesy of the Press-Enterprise.

Silk dalea (Dalea mollisma).

^Creosote desert near Barstow.

Wildlife Habitat

^Desert bighorn sheep.

The wide deserts surrounding Route 66 are full of wildlife as well as views and cultural history. Desert tortoises roam the creosote flats. The black lava of Pisgah holds dark-colored Desert horned lizards, Chuckwallas, and the odd little arboreal Long-tailed brush lizard. Biologists hope to preserve the connectivity of mountains so that Desert bighorn sheep can continue to disperse across the basins and visit distant hills and ranges.

BLM's Steve Borchard said conservationists are overstating the habitat-corridor issue. Bighorn sheep travel miles, not tens of miles, he said, and applying the issue of connectivity on such a large scale is "bunk."

Bighorn dispersals include one-way movements across valleys between mountains to new home ranges. Sheep also journey to water sources over long distances, rams travel between ewe groups, and bands may drift seasonally with return trips. Radio collared sheep have moved to different mountain ranges in search of better food and water, moving 30 to 50 miles (Simmons 1981). According to Krausman et al. (1999), males may movements during the mating season may encompass several mountain ranges, with a straight line distance of as much as 33 miles in one trip.

These are our pubic lands, and should not necessarily be given away to any corporate interest that comes along. Massive development of large scale renewables all over the desert would destroy both habitat and historic heritage.

On the other hand, if this chunk of desert is protected as a monument, other equally diverse and beautiful areas, such as Chuckwalla Valley, will be given up for development. That is why Basin and Range Watch supports localized energy development on rooftops, within the built enviroment, and distibuted generation, over any remote utility-scale development of renewable energy.

^Zebra-tailed lizard (Callisaurus draconoides) at Pisgah Crater.

Long-tailed brush lizard (Urosaurus graciosus) on a creosote.

^Pocket mouse (Perognathus sp.).

^Flowering Goldenbush (Ericameria linearifolia).

^Route 66 in Piute Valley approaching Needles and the Dead Mountains.

^Sheephole Mountains at sunset.

References:

Krausman, Paul, Andrew Sandoval, and Richard Etchberger. 1999. Natural history of the desert bighorn. In, Mountain Sheep of North America, edited by Raul Valdez and Paul Krausman. University of Arizona Press: Tucson.

Simmons, Normann. 1981. Behavior. In, The Desert Bighorn, edited by Gale Monson and Lowell Sumner. University of Arizona Press: Tucson.

^Along Amboy Road, south of Route 66.

^Rattlesnake sculpture along Route 66 in Needles, California.

For more see the story >>here.

Wildlands Conservancy >>here.

National Park Service: Route 66 Listed Among World's And Nation's Most Endangered Places >>here.

Route 66 Magazine >>here.

Route 66 Pulse newspaper >>here.

Smithsonian Magazine story >>here.

HOME..........Solar in the Desert..........The Problem.........The Solution