Defenders of Wildlife Pushes to List Squirrel

April 27, 2010 - A Notice of a 90-day petition finding was announced today, initiating a status review by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) to List the Mohave Ground Squirrel as Endangered with Critical Habitat.

The Mohave ground squirrel (Xerospermophilus mohavensis) will be reviewed to determine if listing is warranted. To ensure that this status review is comprehensive, FWS is requesting scientific and commercial data and other information regarding this species. Based on the status review, FWS will issue a 12-month finding on the petition, which will address whether the petitioned action is warranted. FWS will make a determination on critical habitat for this species, which was also requested in the petition, if and when a listing action is initiated.

Information should be sent on or before June 28, 2010.

ADDRESSES: You may submit information by one of the following methods:

Federal eRulemaking Portal: http://www.regulations.gov.

Search for docket FWS-R8-ES-2010-0006 and then follow the instructions for submitting comments.

U.S. mail or hand-delivery: Public Comments Processing, Attn: FWS-R8-ES-2010-0006; Division of Policy and Directives Management; U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service; 4401 N. Fairfax Drive, Suite 222; Arlington, VA 22203.

FWS will post all information received on http://www.regulations.gov.

FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT: Michael McCrary, Listing and Recovery Coordinator, Ventura Fish and Wildlife Office, 2593 Portola Road, Suite B, Ventura, CA 93003; telephone (805) 644-1766 (805) 644-1766 ; facsimile (805) 644-3958.

SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION:

Information Solicited

FWS seeks information on:

(1) The species' biology, range, and population trends, including:

(a) Habitat requirements for feeding, breeding, and sheltering;

(b) Genetics and taxonomy;

(c) Historical and current range, including distribution patterns;

(d) Historical and current population levels, and current and projected trends; and

(e) Past and ongoing conservation measures for the species, its habitat, or both.

(2) Historical and current survey information on the Mohave ground squirrel, including survey methods and design, time of year, weather information, time of day, site selection method, and descriptions of physical characteristics of landscapes, soil, and vegetation.

(3) The factors that are the basis for making a listing determination for a species under section 4(a) of the Act (16 U.S.C. 1531 et seq.), which are:

(a) The present or threatened destruction, modification, or curtailment of the species' habitat or range;

(b) Overutilization for commercial, recreational, scientific, or educational purposes;

(c) Disease or predation;

(d) The inadequacy of existing regulatory mechanisms; or

(e) Other natural or manmade factors affecting its continued existence.

(4) Information on management programs for the conservation of the Mohave ground squirrel.

(5) Information on current or expected future development within the range of the Mohave ground squirrel, including but not limited to: the extent or magnitude of habitat loss, degradation, or fragmentation from development for energy, transportation, agriculture, military training; land management prescriptions; or recreation, and how they may affect the conservation of the Mohave ground squirrel.

(6) Information on the population status of predators of the Mohave ground squirrel, including information on the occurrence and extent/severity of predation by coyotes, house cats, common ravens, domestic dogs, and feral dogs on the Mohave ground squirrel, and the effect of this predation on the Mohave ground squirrel's long-term survival.

(7) Information on morphological, behavioral, genetic, or ecological variability in the Mohave ground squirrel, and any change in that variability.

(8) Information on environmental change within the range of the Mohave ground squirrel.

(9) Information on the importance of certain areas or populations to the long-term conservation of the Mohave ground squirrel that may help us identify potentially significant portions of the species'

range. This may include information that demonstrates the following factors are important to a portion of the Mohave ground squirrel's range:

(a) The quality, quantity, and distribution of habitat relative to the biological requirements of the species;

(b) The historical values of the habitat to the species;

(c) The frequency of use of the habitat; and

(d) The uniqueness or importance of the habitat for other reasons, such as breeding, feeding, seasonal movements, wintering, or suitability for population expansion, or for genetic diversity.

Please include sufficient information with your submission (such as full references) to allow us to verify any scientific or commercial information you include.

If, after the status review, FWS determines that listing the Mohave ground squirrel is warranted, FWS will propose critical habitat (see definition in section 3(5)(A) of the Act), in accordance with section 4 of the Act, to the maximum extent prudent and determinable at the time FWS proposes to list the species. Therefore, within the geographical range currently occupied by the Mohave ground squirrel, FWS requests data and information on:

(1) What may constitute "physical or biological features essential to the conservation of the species'';

(2) Where these features are currently found; and

(3) Whether any of these features may require special management considerations or protection, including managing for the potential effects of climate change.

In addition, FWS requests data and information on "specific areas outside the geographical area occupied by the species'' that are "essential for the conservation of the species.'' Please provide

specific comments and information as to what, if any, critical habitat you think we should propose for designation if the species is proposed for listing, and why such habitat meets the definition of critical habitat in section 3 of the Act and the requirements of section 4 of the Act.

Petition History

On September 5, 2005, FWS received a petition, dated August 30, 2005, from Defenders of Wildlife and Dr. Glenn R. Stewart to list the Mohave ground squirrel as endangered, and to designate critical habitat concurrently with the listing. In a March 28, 2006, letter to the petitioners, FWS informed them that they would not be able to address their petition at that time because further action on the petition was precluded by court orders and settlement agreements for other listing actions that required FWS to use nearly all of our listing funds for fiscal year 2006. FWS also stated their initial review of the petition did not indicate that an emergency situation existed and that emergency listing was not necessary.

Previous Federal Actions

On December 13, 1993, the Service received a petition dated December 6, 1993, from Dr. Glenn R. Stewart of California Polytechnic State University, Pomona, California, requesting the Service to list the Mohave ground squirrel as a threatened species. At that time, the species was a category 2 candidate (November 15, 1994; 59 FR 58988), and was first included in this category on September 18, 1985. Category 2 included taxa for which information in the Service's possession

indicated that listing the species as endangered or threatened was possibly appropriate, but for which sufficient data on biological vulnerability and threats were not available to support a proposed listing rule. On September 7, 1995, FWS published a 90-day petition finding, which determined that the 1993 petition did not present substantial information indicating that the petitioned action may be warranted (60 FR 46569).

Species Information

The Mohave ground squirrel (Xerospermophilus mohavensis) is a distinct, full species with no recognized subspecies. It was discovered in 1886 by F. Stephens and described as a distinct monotypic species by Merriam (1889, p. 15). The type locality is near Rabbit Springs in the Lucerne Valley, San Bernardino County, California.

The Mohave ground squirrel is a medium-sized squirrel. Total length is approximately 23 centimeters (cm) (9 inches (in)) with a tail length of 6.4 cm (2.5 in). The upper body is grayish brown, pinkish gray, cinnamon gray, and pinkish cinnamon without stripes or flecking. The

underparts of the body and the tail are white (Ingles 1965, p. 171). The skin is darkly pigmented and dorsal hair tips are multi-banded. The closest relative of the Mohave ground squirrel is the round-tailed ground squirrel (Xerospermophilus tereticaudus). It has a contiguous, but not overlapping, geographic range with the Mohave ground squirrel.

Mating and Reproduction

The Mohave ground squirrel mating season occurs from mid-February to mid-March (Harris and Leitner 2004, p. 1). Recht (c.f. Gustafson 1993, p. 83) reported that male Mohave ground squirrels are territorial during the mating season. Females may enter male Mohave ground squirrel

territory and remain for 1 or 2 days. After copulation, the females establish their own home ranges. John Harris (personal communication, Mills College, Oakland, CA, as cited in the petition, p. 14) observed male Mohave ground squirrels staking out the overwintering sites of females to mate with them when they emerged. Gestation is about 30 days with litter size ranging from four to nine (Best 1995, p. 3). Parental care continues through mid-May, with juvenile Mohave ground squirrels emerging above ground between 10 days to 2 weeks later (Gustafson 1993, p. 84). Mortality for juveniles is high during the first year with more male Mohave ground squirrels lost

than females. Female Mohave ground squirrels can breed at 1 year of age if environmental conditions are favorable (Leitner and Leitner 1998, p. 28).

The reproductive success of the Mohave ground squirrel is dependent on the amount of fall and winter precipitation. Leitner and Leitner (1998, p. 20) found a positive correlation between fall and winter rainfall and recruitment of juvenile squirrels the following year. In a low rainfall year, Mohave ground squirrels may forego breeding, or the low availability of food due to low rainfall may cause reproductive failure (Leitner and Leitner 1998, p. 29).

Range and Distribution

The presumed historical range of the Mohave ground squirrel, which is based on the current range and historical locations of suitable habitat, is the northwest portion of the Mojave Desert in parts of

Inyo, Kern, Los Angeles, and San Bernardino Counties, California. This area is bounded on the south and west by the San Gabriel, Tehachapi, and Sierra Nevada ranges, and on the northeast by the Owens Lake and Coso, Slate, Quail, Granite, and Avawatz Mountains. The southeastern edge of the historical range is bordered by the Mojave River with the exception of one locality east of the Mojave River in the Lucerne Valley. The historical range of the Mohave ground squirrel is assumed to have included that area of the Antelope Valley west of the communities of Palmdale, Lancaster, Rosamond, and Mojave, although there are no records of the species being sighted or captured there.

The current range of the Mohave ground squirrel is similar to the historical range, except it excludes the western portion of the Antelope Valley in Los Angeles and Kern Counties and possibly some of the area from Victorville to the south and southeast to Lucerne Valley in San Bernardino County. Urban and agricultural development in these areas has resulted in the loss or modification of Mohave ground squirrel habitat. The Mohave ground squirrel has the smallest range of any ground squirrel species in the United States. Gustafson (1993, p. 8) states the geographic range of the Mohave ground squirrel encompasses approximately 1,968,000 hectares (ha) (4,863,000 acres

(ac)).

Activity Patterns, Movements, and Home Range

The active season for the Mohave ground squirrel is short, generally from early March to August (Bartholomew and Hudson 1960, p. 194), but may begin as early as mid-January to late February.

Initiation depends on temperature and elevation (Gustafson 1993, p. 19). During this time, Mohave ground squirrels must mate, gather enough nutrition to produce and sustain a litter, and ensure nutritional reserves to last during the inactive season. During the inactive season, Mohave ground squirrels exist in their burrows in a state of torpor (a state of reduced physiological activity or sluggishness) to conserve their reserves of energy and water. The length of the active season varies by sex, age, and availability of food resources. In dry years, which are often non-reproductive years, Mohave ground squirrels may enter their state of torpor as early as spring (Leitner et al. 1995, p. 83). The active season for an adult is shorter than for a juvenile as adults do not need to acquire as much energy for the inactive season as juveniles do. The active season for an adult female is generally longer than for a male because females need to acquire additional energy for litter production and lactation (Leitner et al. 1997, pp. 114-115).

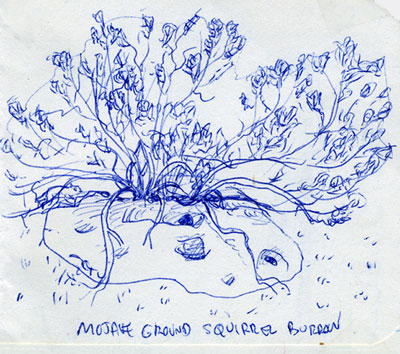

Mohave ground squirrels are diurnal; they spend much of the day above ground (Recht 1977, p. 56). As temperatures increase into the spring and early summer, Mohave ground squirrels will spend more time in the shade of shrubs or briefly use their burrows. Burrows are usually located beneath large shrubs. Mohave ground squirrels may use several burrows at night throughout a season; they also use other burrows for predator avoidance and temperature regulation. The burrow used for the inactive season is dug specifically for that period (Recht 1977, p. 9).

Mohave ground squirrels exhibit a behavior called natal dispersal. Upon dispersing from the burrow where they were born, some males will move and take up residence at least 1,009 meters (m) (3,280 feet (ft)) from the natal burrow while females move a shorter distance of 200 to 300 m (650 to 980 ft) from their natal burrows (Leitner and Leitner 1998, p. 34; Harris and Leitner 2005, p. 191). The home range of the Mohave ground squirrel varies among years and between sexes during the mating season. The mean home range is 0.74 ha (1.83 ac) for mating females and 6.73 ha (16.63 ac) for males. Outside the breeding season, the mean home range size is 1.20 ha (2.96 ac) for females and 1.24 ha (3.06 ac) for males (Harris and Leitner 2004, pp. 520-521).

Population Demographics

The behavioral characteristics of the Mohave ground squirrel, as discussed above, make it difficult to determine or estimate population status and trends because the species spends much of the year underground and populations appear to be sensitive to both seasonal and annual rainfall patterns. That is, in dry years or dry fall seasons, reproduction during the following spring season may be unsuccessful and population size may contract (Leitner and Leitner 1998, pp. 29-31).

Survey results suggest that the Mohave ground squirrel has a patchy distribution throughout its range (Hoyt 1972, p. 7; Gustafson 1993, p. viii). Most reported information describes the number of animals trapped or number trapped as compared to the trapping effort. We are aware of only one location where information on population trend was available (Leitner 2005, p. 3). In the northwest portion of the range of the Mohave ground squirrel, trapping results are available for the Coso Range within China Lake Naval Air Weapons Station (NAWS). The surveys span 1992 to 1996 and 2001 to 2005. The total number of Mohave ground squirrels captured during the first survey period was more than twice that of the second (Leitner 2005, p. 3). Brooks and Matchett (2002) analyzed the data from all known Mohave ground squirrel studies. Forty-nine percent of the sites were identified from observing or trapping only one animal.

Habitat and Life History Requirements

The habitat requirements of the Mohave ground squirrel are varied. The species has been found in a variety of vegetative communities including Mojave Creosote Scrub, Desert Saltbush Scrub, Desert Sink Scrub, Desert Greasewood Scrub, Shadscale Scrub, and Joshua Tree (Yucca

brevifolia) Woodland (Gustafson 1993, pp. ix, 81). Creosote Bush Scrub is the vegetation community in which the Mohave ground squirrel is most often found. Mohave ground squirrels usually inhabit flat to moderately sloping terrain. They prefer deep rather than shallow soils and

gravelly soils rather than sandy soils (Aardahl and Roush 1985, p. 23). Soil characteristics are important as the Mohave ground squirrel constructs burrows for temperature regulation, predator avoidance, and inactive season use.

The food habits of the Mohave ground squirrel are diverse. Recht (1977, p. 80) called the Mohave ground squirrel a facultative specialist; its foraging strategy falls between that of a specialist

and a generalist. The Mohave ground squirrel specializes in foraging on certain plant species over short periods of time. As the availability of forage species changes throughout the active season, the Mohave ground squirrel adapts its foraging strategy to maximize energy intake in a changing environment. Observations and fecal analysis indicate that Mohave ground squirrels consume a variety of annual and perennial plants and arthropods (Leitner and Leitner 1992, p. 12; Gustafson 1993, pp. 77-83). At one study site, the leaves of three shrub species made up 60 percent of the Mohave ground squirrel diet based on fecal analysis (Leitner and Leitner 1998, p. 34). In a study by Leitner and Leitner (1992) in the northern part of its range, the Mohave ground squirrel was found to consume leaves of annual and perennial plants, their fruits and seeds, fungi, and butterfly larvae. Mohave ground squirrels appear to exploit food sources that are available on an

intermittent basis. They may also select particular food items over others because of higher water content. Leitner and Leitner (1992, p. 25) concluded that the Mohave ground squirrel is flexible in exploiting high-quality food resources.

Predation and Mortality

There is little documentation on the natural predators of the Mohave ground squirrel. There is circumstantial evidence of predation by coyotes (Canis latrans), prairie falcons (Falco mexicanus), and common ravens (Corvus corax) (Leitner et al. 1997, p. 49; J. Harris, personal communication, as cited in the petition, p. 15). There may be other natural predators of the Mohave ground squirrel. Mortality is high for the Mohave ground squirrel during the first year and appears to be skewed toward males (Brylski et al. 1994, p. 64; Leitner and Leitner 1998, p. 28). Mortality may also be caused by extended periods of low amounts of fall and winter rainfall, which

results in reduced availability of forage and water, and can increase vulnerability to disease.

Evaluation of Information for This Finding

A species may be determined to be an endangered or threatened species due to one or more of the five factors described in section 4(a)(1) of the Act: (A) The present or threatened destruction,

modification, or curtailment of its habitat or range; (B) overutilization for commercial, recreational, scientific, or educational purposes; (C) disease or predation; (D) the inadequacy of existing regulatory mechanisms; or (E) other natural or manmade factors affecting its continued existence.

FWS's evaluation of this information is presented below.

A. The Present or Threatened Destruction, Modification, or Curtailment of the Species' Habitat or Range:

The petitioners presented information regarding threats to the Mohave ground squirrel from reduced range and habitat destruction, including: urban and rural development on private and public lands; agricultural development; military activities; livestock grazing; transportation; energy

development; and that the cumulative impacts of drought, habitat destruction, habitat fragmentation, and decrease in precipitation with climate change pose a threat greater than the drought episodes to which the Mohave ground squirrel is adapted. The range of the Mohave ground squirrel is the smallest of all ground squirrels in the United States. Based on information provided by the petitioners, the Mohave ground squirrel appears to have been nearly extirpated from the southern portion of its range, which represents approximately 20 percent of its range (Leitner as cited in the petition, p. 8). This assertion is based on the results of surveys conducted for the Mohave ground squirrel from 2002 to 2004 (Leitner 2004 as cited in the petition, p. 17). The portion of the recently reduced range includes an area south of State Highway 58 in the

Palmdale-Lancaster area and the Victorville to Lucerne Valley area.

Private Lands

On private lands, which comprise about 31 percent of the current range of the Mohave ground squirrel, the petitioners claim 2.8 percent of the range of the Mohave ground squirrel has been lost to urban and rural development and approximately 2 percent (37,000 ha (92,000 ac)) to agricultural fields. The information on impacts to the Mohave ground squirrel from agricultural development was derived from Hoyt (1972, p. 8), Aardahl and Roush (1985, p. 2), and Gustafson (1993, pp. 23-24). The petitioners also stated that they have no updated data to quantify the extent or intensity of this threat. FWS says it has no information in their files to dispute the figures presented by the petitioners; however, they say they currently do not have information to determine whether a 2.8 percent loss to urban and rural development and a 2 percent loss to

agricultural development is biologically significant to the Mohave ground squirrel.

Public Lands

Public lands managed by the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) account for about 31.8 percent of the species' range. The petitioners stated that BLM's land management plan for the West Mojave Desert (West Mojave Plan) would allow new development throughout much of the range of the

Mohave ground squirrel and would not protect the four Mohave ground squirrel "core areas'' (see petition, p. 17). "Core areas'' are defined by the petitioners as locations where Mohave ground squirrels have been reliably captured over time, or where there are thriving populations. The petitioners stated that activities that result in the loss of habitat in these "core areas'' or prevent dispersal among these "core areas'' will impede and eventually prohibit conservation of the Mohave ground squirrel. Public land managed by the Department of Defense accounts for about 34.5 percent of the species' current range. The petitioners stated that current military training at Fort Irwin threatens Mohave ground squirrels by crushing animals, compacting and otherwise disturbing

soils, collapsing burrows, destroying shrubs used for cover, and reducing spring annual plants used by Mohave ground squirrels for forage (Bury et al. 1977, pp. 16, 18). According to the petitioners,

Fort Irwin's training currently affects 7.4 percent of the range of the Mohave ground squirrel, and the proposed expansion of Fort Irwin will affect additional lands within the range of the Mohave ground squirrel and will fragment one of the four Mohave ground squirrel "core areas'' as identified by the petitioners. Additionally, 2.7 percent of the current range of the Mohave ground squirrel occurs on other public 'protected lands' (see petition, p. 40) including; federally designated wilderness areas, State park land, California Department of Fish and Game land, and the Desert Tortoise Natural Area.

Livestock Grazing

The petitioners stated that livestock grazing has the potential to degrade Mohave ground squirrel habitat through changes in soil structure, including accelerated erosion and collapsing burrows,

changes in vegetative structure, reduced availability of native forage species (Laabs 2002, p. 5; Campbell 1988, pp. 569, 574), and direct competition with Mohave ground squirrels for limited quality and quantity of forage (Leitner and Leitner 1998; pp. 29, A6, A7, A15, and A23). According to the petitioners' GIS analysis, 27 percent of the range of the Mohave ground squirrel has been impacted by livestock grazing. Aardahl and Roush (1985, p. 23), as cited in the petition, stated

that "land uses which affect the availability of forbs and grasses have the potential to influence the long-term population of the Mohave ground squirrel,'' but this does not "mean that properly managed livestock grazing will cause a significant negative impact on the Mohave ground squirrel.'' Twenty-one of 22 study sites surveyed were grazed by sheep or cattle in varying degrees; the study site with the highest total adjusted captures of Mohave ground squirrels showed considerable signs of grazing (Aardahl and Roush 1985, p. 23). The petitioners did not provide information, and we have no information in our files, on the extent or magnitude of the impacts of livestock

grazing on the Mohave ground squirrel.

Transportation

The petitioners identified the extensive network of highways and roads in the range of the Mohave ground squirrel as a threat. The petitioners claim impacts from highway and road establishment and vehicle use include habitat loss, fragmentation, and degradation, and direct mortality from vehicle strikes (Gustafson 1993, pp. 23, 26; BLM 2003, p. 30; Leitner as cited in the petition, p. 22). The petitioners stated that there is evidence of surface disturbance to roadsides up to 400 m (1,312 ft) away from the road, and that 37 percent of transects conducted by the BLM in the West Mojave Desert were bisected by roads. The petitioners calculated that the total area of the network of roads and highways affected 65,964 ha (163,000 ac) or 3.3 percent of the range of the Mohave ground squirrel. The petitioners provided additional information that impacts from roads on the desert tortoise have been documented more than 3,962 m (13,000 ft) from the highest

level traffic road (Hoff and Marlow 2002, p. 454) and that similar impacts likely occur to the Mohave ground squirrel. FWS does not agree that impacts to the desert tortoise from roads that

have been measured more than 3,962 m (13,000 ft) from the highest traffic roads are the same as those to the Mohave ground squirrel. The Hoff and Marlow study (2002, p. 454) reported on the abundance of desert tortoise sign at intervals from roads. This study was specific to the desert tortoise, and FWS argues it did not examine the effects of roads on the Mohave ground squirrel. However, FWS does agree with the petitioners that roads and highways result in direct mortality to Mohave grounds squirrels from vehicle collisions and habitat loss and degradation.

Energy Development

According to the petitioners, geothermal exploration and development and the construction ofsolar energy plants in the range of the Mohave ground squirrel have caused, and will likely cause, adverse impacts to the Mohave ground squirrel and loss or degradation of habitat (Leitner and Leitner 1989, p. 2). The petitioners did not quantify the amount of habitat affected. FWS acknowledges that energy development for geothermal and solar energy has occurred within the range of the Mohave ground squirrel and that this development can result in the degradation or loss of habitat used by the Mohave ground squirrel. The petitioners do not provide information, and FWS says it does not have information in their files, on the extent of this loss or degradation and how it will affect the conservation of the Mohave ground squirrel. [We note that the petition was filed before large-scale renewable energy development came on the scene. Land acreages can easily be quantified now using BLM and Energy Commission maps and data - BRW]

Cumulative Impacts of Habitat Destruction, Fragmentation, and Decreased Precipitation

The petitioners provided information that indicates the reproduction and survival of the Mohave ground squirrel is ultimately linked to rainfall (Harris and Leitner 2004, pp. 517, 518). Mohave

ground squirrels may fail to persist in certain areas during drought episodes (Leitner and Leitner 1998, p. 31). The petitioners assert the cumulative impacts of habitat destruction, habitat fragmentation, and overall decrease in precipitation due to climate change are a greater threat to the Mohave ground squirrel than the periods of low rainfall and drought episodes with which the Mohave ground squirrel evolved. Based on information from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (Watson et al. 2002, pp. 8, 9), FWS acknowledges temperatures in southern California are likely to increase and precipitation is likely to decrease in the future. With hotter, drier conditions and more extreme weather patterns in southern California than those with which

the Mohave ground squirrel evolved, the species may be negatively affected. However, FWS believe that climate change models that are currently available are not yet capable of making meaningful predictions of climate change for specific, local areas such as the range of the Mohave ground squirrel (Parmesan and Matthews 2005, p. 354). FWS is not currently aware of models that predict how climate in the range of the Mohave ground squirrel will change, and they say they do not know how any change may alter the range of, or otherwise threaten, the species.

FWS found the petition and information in their files presents substantial information that these activities may have contributed to a recent range contraction in the southern portion of the Mohave ground squirrel's range, and may threaten the Mohave ground squirrel across its current range by removing shrubs needed for cover and forage, disturbing soil, or removing or degrading other habitat features necessary for Mohave ground squirrel life history requirements. Additionally, one or more of these activities may threaten what the petitioners identify as "core areas'' for the Mohave ground squirrel by removing habitat, fragmenting the habitat, and preventing dispersal among the "core areas.''

But FWS determined the petition does not present substantial information indicating that climate change may be a threat to the species. Additionally, information on the subject of climate change in their files is not specific to the Mohave ground squirrel. They say they will evaluate the effects of climate change, including reduced precipitation and any cumulative effects of habitat fragmentation or loss on the Mohave ground squirrel, when we conduct our status review.

On the basis of our evaluation of the information in the petition and information in our files, FWS determined that the petition presents substantial information indicating that listing the Mohave ground squirrel as endangered may be warranted due to destruction, modification, or curtailment of the species' habitat or range.

Overutilization for Commercial, Recreational, Scientific, or Educational Purposes

The petitioners did not provide information or list any threats to the Mohave ground squirrel from overutilization for commercial, recreational, or educational purposes. The petitioners stated that the utilization of the Mohave ground squirrel for scientific purposes is strictly controlled by the California Department of Fish and Game.

Disease or Predation

The petitioners did not provide information or list any threat to the Mohave ground squirrel from disease, and we do not have information in our files regarding potential threats to this species due to disease. The petitioners stated that there is little documentation of the Mohave ground squirrel's natural predators, but claimed that predation by coyotes, common ravens, house cats, domestic dogs, and feral dogs is a concern. Although the petitioners stated that cats prey on small mammals and dogs dig up rodent burrows, they did not present any information on the level of mortality or population impacts from predation for Mohave ground squirrels, any other ground squirrel species, or any small mammal species. The petitioners noted that the numbers of common ravens and coyotes, known predators of the Mohave ground squirrel, have increased, posing an increased predation risk to Mohave ground squirrel populations.

The Inadequacy of Existing Regulatory Mechanisms

The petitioners stated that current regulations have proven inadequate to conserve the Mohave ground squirrel; that only 9 percent of the range of the Mohave ground squirrel has any kind of protected status; and that, although the Mohave ground squirrel is a State-listed species, this listing provides no conservation assurances for the Mohave ground squirrel on Federal lands.

The California Endangered Species Act provides protection for the Mohave ground squirrel on private and State-owned land, and on Federal lands in relation to activities carried out by non-Federal entities that are required to obtain a State permit or authorization. The major military installations within the range of the Mohave ground squirrel have implemented Integrated Natural Resources Management Plans that cover the Mohave ground squirrel and implement actions to manage for the species. In their management plan for the West Mojave Desert, the BLM considers the Mohave ground squirrel an umbrella species, a species whose habitat requirements include those of many other species and whose conservation should automatically conserve a host of other species. BLM has implemented a plan that establishes a Mohave ground squirrel Conservation Area that contains 35 percent of the species' historical range on BLM land.

But FWS determined that the petition does not present substantial information indicating that listing the Mohave ground squirrel as endangered may be warranted due to the inadequacy of existing regulatory mechanisms.

Other Natural or Manmade Factors Affecting the Species' Continued Existence

The petitioners stated that pesticide use may adversely affect the Mohave ground squirrel. According to the petitioners, Mohave ground squirrels live in native vegetative communities adjacent to agricultural fields and other areas where rodenticides are used. Mohave ground squirrels use these areas for forage and shelter. The petitioners claim that if rodenticides are used on agricultural fields, Mohave ground squirrels could be adversely affected, or they could be

exterminated by the State Rodent Program. In the early part of the 20th century, the Los Angeles Agricultural Commission used poison grain to target and eliminate ground squirrels in the Antelope Valley, which includes the historical range of the Mohave ground squirrel. Strychnine is the active ingredient.

Finding

FWS says there is substantial information to indicate habitat based threats that may remove shrubs needed for cover and forage, disturb soil, or remove or degrade other habitat features

necessary for Mohave ground squirrel life history requirements across its current range.

If the threat is significant, it may drive or contribute to the risk of extinction of the species such that the species may warrant listing as threatened or endangered as those terms are defined by the Act. This does not necessarily require empirical proof of a threat. The combination of

exposure and some corroborating evidence of how the species is likely impacted could suffice. The mere identification of factors that could impact a species negatively may not be sufficient to compel a finding that listing may be warranted. The information shall contain evidence sufficient to suggest that these factors may be operative threats that act on the species to the point that the species may meet the definition of threatened or endangered under the Act.

Because FWS found that the petition presents substantial information that listing the Mohave ground squirrel may be warranted, they are initiating a status review to determine whether listing the Mohave ground squirrel under the Act is warranted. FWS will issue a 12-month finding as to whether the petitioned action is warranted.

References Cited

A complete list of all references cited is available on the Internet at http://www.regulations.gov and upon request from the Ventura Fish and Wildlife Office.

From the Federal Register Online via GPO Access [wais.access.gpo.gov](Volume 75, Number 80)]

[Proposed Rules][Page 22063-22070]

West Mojave Natural History

^Mojave Ground Squirrel

By LC

The Mojave ground squirrel (Spermophilus mohavensis) is listed as endangered under the California Endangered Species Act but not the federal Endangered Species Act (yet). The little squirrels are quite elusive, and even biologists have a difficult time studying them. The Bureau of Land Management lists at least 60 proposals for public lands in the 10.4 million-acre California Desert district.

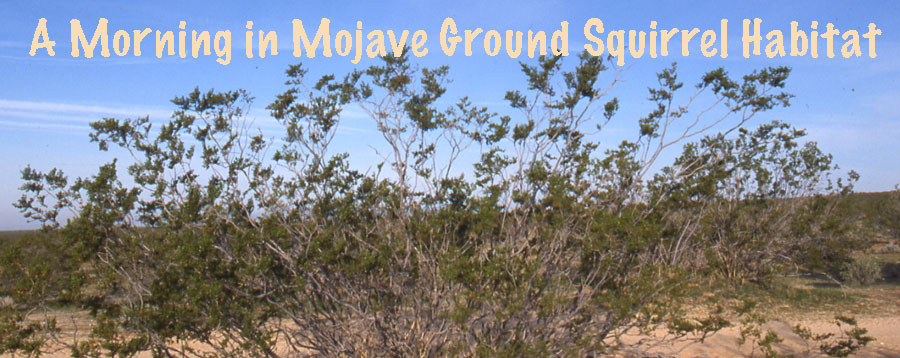

^Large scattered Joshua trees (Yucca brevifolia) in a saltbush flat of Allscale (Atriplex polycarpa), habitat for Mojave ground squirrels in the San Bernardino County western Mojave Desert.

The best place to put solar power plants could be slowed down by "some animal life!" -- Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger on 60 Minutes, December 21, 2008.

Exploring Mojave Ground Squirrel Deserts

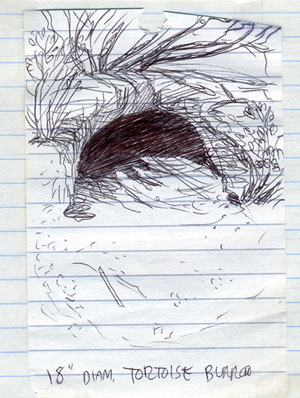

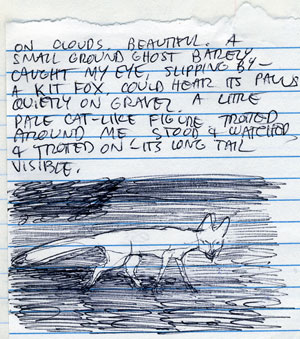

I took several walks around the West Mojave, photographing, sketching, observing. I saw a Mojave ground squirrel only once, dashing on a shrubby gravel flat (above) into its burrow system under a creosote (I got out my notepad and made a drawing of the burrow, below). Just because you don't see them doesn't mean they aren't there, I thought.

The Mojave ground squirrel has a small total range, only dwelling on sandy and gravelly desert scrub flats and hills of San Bernardino, Los Angeles, Kern, and Inyo counties. It eats seeds, herbs, leaves of shrubs such as saltbush, and Joshua tree fruits. These small rodents have adapted to the harsh desert by going dormant in their underground burrows during the extreme heat of summer and the cold of winter - they are usually seen only in late winter and spring.

"Populations are reduced by urban development, off-road vehicle use, and agriculture," according to the California Department of Fish and Game.

See the article in Tortoise Tracks.

One thing I learned getting up early in the morning to enjoy the desert dawn, was how rich in life this place is. Hundreds of kinds of plants, wildflowers, insects, lizards, birds, and mammals call the West Mojave home. It is not an empty wasteland, ready for the bulldozer to build power plants. It is a bonanza of diversity. Following are some photos and sketches of places from around Victorville, Palmdale, and north to Ridgecrest and the Coso Mountains, all in the range of the Mojave ground squirrel.

^A large orange-and-black beetle dines on he seedpod of a Paperbag bush (Salazaria mexicana).

^Delicate flowers of Wishbone bush (Mirabilis californica).

^An entomologist showed my this ant-mimic wasp from the Coso Mountains he had just caught in his net.

^A milkvetch (Astragalus sp.) blooms in spring on the gravelly desert floor.

^I saw this amazing striped blackish Leopard lizard (Gambelia wislizenii) one morning, and sketched it before it ran. Normally they are yellow with black leopard-spots. Kern County.

^A LeConte's thrasher scrurried into the saltbush.

^Saltbush and creosote habitat near Victorville.

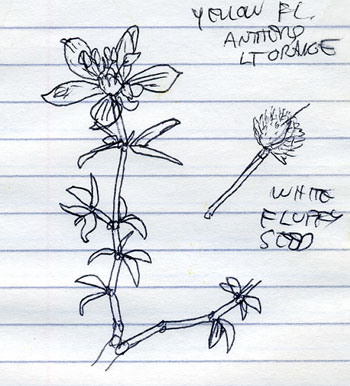

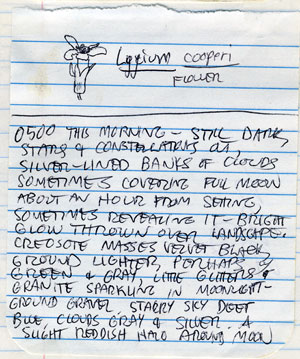

^Squirreltail grass (Elymus elymoides) and flowering Goldenbush (Ericameria cooperi).

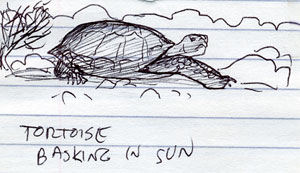

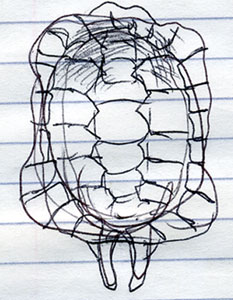

^Prime active burrow of a Desert tortoise (Gopherus agassizii), and nearby, the tortoise basking (below).

^Joshua tree desert near Palmdale.

The Mojave blooms in springtime: Desert dandelion (Malacothrix glabrata) and Desert pincushion (Chaenactis sp.).

^Creosote (Larrea tridentata) flowers.

^Desert dandelion fields near Ridgecrest, with the Sierra Nevada looming in the background.

^Spectacular Thistle sage (Salvia carduacea).

^Popcorn flower (Plagiobothrys sp.).

^Rock art.

^Desert dawn.

^Notes about an encounter with a Kit fox.

^The Woldfberry bushes (Lycium cooperi) were in full bloom that spring. These turned into delicious berries later on.

^Lacy phacelia (Phacelia tanacetifolia).

^Saltbush and Joshua trees bathed in low sunlight and blue shadows, near Victorville.

^Golden gilia (Linanthus aureus) next to the Mojave ground squirrel burrow I sketched.

^Mushrooms in the desert? Strange Puffballs emerge out of the ground after a rain.

^Various bird nests in low desert shrubs: Sage sparrow, LeConte's thrasher, and Cactus wren. Also, a cousin of the Mojave ground squirrel, the White-tailed antelope ground squirrel (Ammospermophilus leucurus), digging in the dirt.

^Coso Range Mojave ground squirrel habitat: Joshua trees in Blackbrush scrub (Coleogyne ramosissima).

^ A shell of a large, old Desert tortoise, lying on the sand.

^Dew-dropped annual lupine (Lupinus sp.).

Is this the Future of the Mojave Desert?

Comments? Sign Our Guest Book ![]()

HOME..........Solar in the Desert..........Renewable News