Mojave Ground Squirrel Concerns

May 4, 2010, Ridgecrest, California - (PREVIOUS PAGE) A two-day California Energy Commission (CEC) workshop on biological resource issues on the Ridgecrest Solar Power Project proposed by Solar Millennium LLC ended in deadlock over the contentious issue of wildlife connectivity between core populations. The second day, covered on this page, concentrated on the small squirrel endemic to the western half of the Mojave Desert. The first day (May 3) was spent on the Desert tortoise.

Dave Hacker of the California Department of Fish and Game (DFG) started out with a presentation on the Mojave ground squirrel (Xerospermophilus mohavensis) issues around the project region, and why he considered this the sticking point for approval. Solar Millennium had agreed to assume presence of the species, as trapping the little rodents is very difficult and time consuming, and DFG would not concur with absence using a reduced trapping effort.

Squirrels have been trapped along Highway 178 towards Trona, in the eastern Fremont Valley, in various spots in Indian Wells Valley, and in a cluster of spots in the Little Dixie Wash area, a core population. No records exist for the project site, but habitat is similar to areas squirrels have been found in.

Squirrels have been trapped along Highway 178 towards Trona, in the eastern Fremont Valley, in various spots in Indian Wells Valley, and in a cluster of spots in the Little Dixie Wash area, a core population. No records exist for the project site, but habitat is similar to areas squirrels have been found in.

Mojave ground squirrels are found mostly in flat valleys under 5% slope (occasionally to 10% slope), low creosote bush scrub, and sometimes in saltbush (Atriplex) scrub. Alluvial soils are needed to burrow in, and the animals do not occupy stony or rocky sites.

The Importance of Connectivity

Hacker explained that as local populations are lost, linkages are lost. Connections between metapopulations (local populations) need to be kept intact.

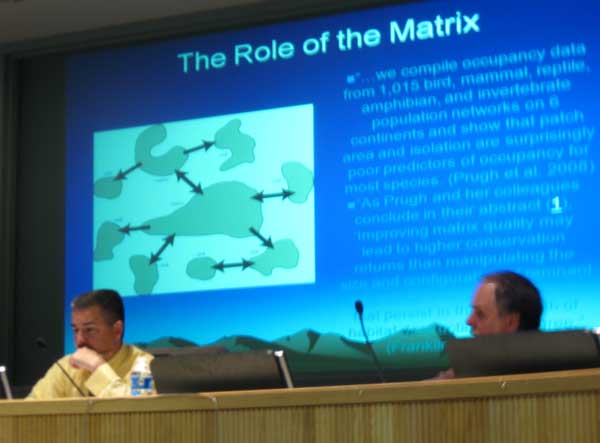

In the past biologists looked at the size and quality of patches, but now there is more interest in the areas between the patches, the "matrix." The size and quality of habitat patches has been shown in studies to be a poor predictor of occupancy. The matrix may be more important, the areas between that provide connectivity.

Connectivity ensures gene flow. Genetic studies by Marjorie Matocq out of the University of Nevada, Reno, show some isolation of the Little Dixie Wash and Coso populations of Mojave ground squirrels, but also evidence of ongoing exchange between all groups, including the Little Dixie Wash local population.

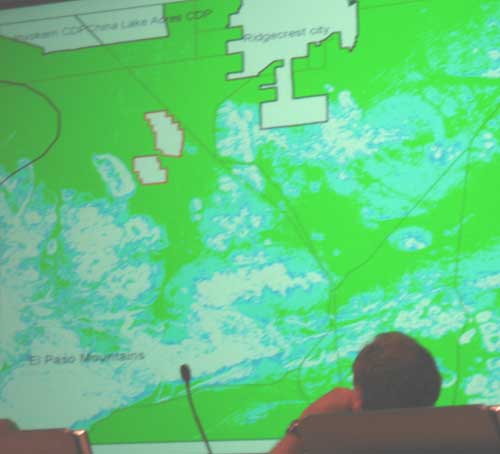

<Range map of the Mojave ground squirrel. Blue areas are military lands, green areas are Mojave ground squirrel conservation areas. Blue circular areas are Core Areas, dashed circular areas area other clusters of records. The project site is indicated in black outline.

Hacker showed a map with arrows indicating connectivity from the Edwards Air Force Base populations to the south, up along Highway 395 through a narrow gap in the El Paso Mountains and hills south of Ridgecrest, northwards to Little Dixie Wash Core Area and the Coso Range.

The trouble with the project, he said, was that it lay squarely in the midst of the connectivity corridor between the northern populations and the whole southern range of the species. The El Paso Mountains formed a barrier, as suitable habitat was apparently very patchy. Ridgecrest development blocked passage to the east of the gap. The project reduced an approximately 13,000-foot wide valley area to two small connectivity gaps the 1,000-foot El Paso Wash between the two solar fields, and a 500-foot gap between the southern solar project and the lava hills to the west, part of the El Paso Mountains. The project footprint would be nearly three square miles across Mojave ground squirrel habitat.

This reduces chances for the squirrel to disperse. Most dispersal events go through suitable habitat, Hacker continued. The California Endangered Species Act (CESA) requires mitigating all impacts, not just replacing individuals. "How do you replace connectivity?" he asked.

Hacker said the world expert on the Mojave ground squirrel, Dr. Phil Leitner, wrote in his 2008 status report that this area where the project proposal sits was identified specifically for connectivity with the Little Dixie Wash Core Area.

>Map showing elevations around the project site in red outline: green is flat valleys, white is mountains. Little Dixie Wash Core Area is curved line to the left. City of Ridgecrest to the right.

Experts Clash

Next Dr. Leitner, pre-eminent expert on the Mojave ground squirrel, spoke for Solar Millennium, defending the applicant's project location. He emphasized that the lack of empirical data handicaps discussion of impacts and mitigation. We do not know how many squirrels are on the project site, if any, he said. Nor do we know how they use the area, as no trapping was carried out. He did think it was probable they used the site, however, since they were present north and south. The project site could support home ranges, he said.

His assessment of the habitat on the site was that it was "not that great" with large areas of open creosote. The southwest corner and El Paso Wash had habitat that was "quite good." We walked the project site, however, and both north and south fields had many indicator plants that grow in good quality Mojabe ground squirrel habitat.

Recent records of Mojave ground squirrels occurred in the Desert Tortoise Natural Area, Pilot Knob, Kramer Junction, and north of Ridgecrest. There are a couple of recent visual observations on China Lake Naval Air Weapons Station, in the north valley, but not enough studies are done there to know much, Leitner said.

The connectivity issue was important, he admitted, such as the Highway 395 area. Edwards AFB has the only decent population, and the area between Kramer Junction and Ridgecrest is important.

>Dr. Leitner speaks to the panel.

Leitner disacussed his research findings. Sites in the Coso Range have squirrels up to 5,000 feet elevation in alluvial basins with low slope. Radiotelemetered young animals have been tracked dispersing over steep rocky terrain, and can even travel 6 to 8 kilometers when a few months old. This phase of life only happens for one to two months, then adults settle down in level alluvial soils.

Leitner detailed the life history of the Mojave ground squirrel. Adults are asleep underground for half the year, in the cold of winter and heat of summer. They come out in February, mating ensues, the males moving relatively long distances (thousands of meters) in February and March. Normal home ranges are 1 to 2 acres. But males may cover half a square mile in the mating season. Females have a 30-day gestation, and in March females prepare a natal burrow. They nurse into early May. By late May and early June a certain percentage of few-month-old juveniles tend to disperse, and can travel 6 to 8 km. One young male radiocollared in Kramer Gulch moved northwards to fairly close to the project area, established his home range, and the next year researchers found babies.

If winter rains are less than 3 inches the population can crash, and survivorship is poor. There may be local extinctions.

Females tend to stay in the area where they were born, but a certain number disperse long distances, and this would allow areas to be recolonized.

Scott Galati, attorney for Solar Millennium, asked Leitner to address the question of whether the project was stopping connectivity.

Scott Galati, attorney for Solar Millennium, asked Leitner to address the question of whether the project was stopping connectivity.

Leitner answered that "We don't really know if Mojave ground squirrels are there, whether they are there every year, or just occasionally." It is just map assumptions of connectivity now, and there is no data to back that up, he contended.

More discussions seemed to confuse connectivity with a certain number of juvenile animals moving through the site. Arguments then broke out about how old the squirrel records were for the surrounding areas. Dick Anderson said that within a 10-mile radius there were 26 records from the California Natural Diversity Database.

Galati said they assumed the ground squirrels were on the project site and would mitigate for them, but this does not prove function and value of connectivity.

<Brittlebush (Encelia farinosa) blooms along the southwestern edge of the project, May 2010.

The debate got heated as Dave Hacker of DFG argued that the project site was suitable habitat connecting suitable habitat. Galati argued back -- "There are other ways to connect!"

Hacker stated that this was a flat valley connectivity area that would have a three-square-mile chunk taken out. Then connectivity would have to rely on infrequent dispersal events through steep rocky areas around the project or narrow spots at the edges of the project. This was not a good way to insure connectivity. Connected home ranges are needed.

Galati tried to argue that most of the project site was not good quality habitat.

Dick Anderson, biologist for the California Energy Commission, said that we don't know a lot about Mojave ground squirrel connectivity, and that this would be important in writing a recovery plan (the US Fish and Wildlife Service announced its 90 day Finding on April 27, 2010, to list the squirrel as Federally Endangered). Anderson asked Leitner, "Do you think we should be cautious with the lack of information?"

Leitner answered, "In the absence of data do we apply the cautionary principle? In general, yes." But he went on to argue that other possibilities for connectivity should be looked at. It is best to maintain the broadest, widest connections, he admitted, but stated we "have a project, and the commissioners must make a decision."

Anderson said this was risky.

Leitner continued to show maps of two broad connectivity arrows passing over the El Paso Mountains north to south, and over the hills south of Ridgecrest (see map below, wide blue arrows). Gaps between the El Paso foothills could allow the squirrels to access Little Dixie Wash from the 395 corridor without needing to pass through the project area, he claimed.

<Power Point presentation by Dr. Leitner on potential connectivity corridors between Mojave ground squirrel populations north and south of the Ridgecrest solar project site. CEC staff look on.

Many people piped up at this proposal. Dave Hacker of DFG argued that he had driven through this saddle through the lava formation and it is narrow. "Is that where you'd put your money on maintaining connectivity?" The most viable connectivity areas are the broadest, he said. "Why are you including mountains?" he asked -- mountains and playas are considered barriers to the ground squirrel in the conservation priority paper DFG was drafting, which Leitner helped with.

Leitner replied, "There are mountains, and there are mountains." He claimed dispersing juveniles could make the passage.

Hector Villalobos, Field manager of the Ridgecrest Bureau of Land Management office, seemed doubtful. He asked about powerlines being moved into the narrow gap between the project west edge and hills, about differing vegetation in the El Paso Mountains, and pointed out cumulative impacts of wind energy project applications west and south of the project.

Galati pushed back, saying they could pull back, do 2 to 3 years of study, or they could move the project forward with dialog. Solar Millennium could fund region wide studies, mitigation, monitoring of connectivity through El Paso Wash, enhancement of the western corridor, and enhance other core areas. "Is there a way to go forward?"

>Winterfat (Krascheninnikovia lanata) fluffy seedheads. An indicator plant of good Mojave ground squirrel habitat. Photo taken on the project site south field. We also found it on the north field. May 2010.

Eric Solorio, CEC project manager on the case, reminded him that Energy Commission regulations had a 12-month deadline for applications. They could not do 2 to 3 years of study without starting over.

We asked Dr. Leitner what he thought the cumulative impacts would be to the ground squirrel if the many renewable projects were built across its range? He answered that "obviously it would be bad to have no limit on renewables."

Solorio said that of 14,000 megawatts (MW) of renewable projects clustered in the region, 30 of 36 projects have dropped out, and the number is down to 2,000 MW. We must counter that this does not prevent new applications from coming in to those same areas.

Leitner went on to say that Mojave ground squirrel populations were high in the 1980s, with 20 to 40 on his study site in the Coso Range. This decade was drier, and he found only half a dozen. Galati pitched in again that they could fund regional connectivity studies, and even move squirrels north to south if the project blocked them.

Hacker of DFG demanded: no baseline data exists. "How do you know what the impacts will be?" He also asked how impacts could be rectified once they happened?

Galati countered that assumes there will be impacts.

Hacker held up research books on connectivity conservation and corridor ecology, stating that there is a lot of research around the world -- it is not an assumption.

<Spiny hopsage (Grayia spinosa) colorful seeds. Photo taken on the northern project site.

Eric Solorio said they should assume some level of connectivity, but wanted to now what baseline to use for mitigation: ten or ten thousand juveniles crossing the site?

Hacker said you could never get that. "We use suitable habitat."

Solorio pressed how they needed to quantify or qualify this in order to develop a mitigation plan. CESA comes down to functions and values, he said, and the applicant is trying to dialog on how to mitigate this.

Dick Anderson would not budge -- "Choose a good alternative brownfield site."

Galati said everyone loves to point to this, but that is not fast either, there are problems too.

Anderson said there is not a way to mitigate for this site. "Site, site, site" he emphasized. It is an important species, he emphasized.

Hacker of DFG explained he was working on dozens of brownfield sites in the state. Most required no take permit, some do, but the impacts to listed species were very much less.

Hacker of DFG explained he was working on dozens of brownfield sites in the state. Most required no take permit, some do, but the impacts to listed species were very much less.

Galati argued, "We are talking about more than your take permit. We have many other permits -- 23. That does not make it easier."

Hacker disagreed, saying issues were a lot easier on brownfields, and in general they were quicker.

>Map showing green and blue dots of Mojave ground squirrel records around the project site in red. Areas to the east of Highway 395 are more developed and would not serve as good habitat, according to CEC and DFG biologists.

Ground Squirrel Translocation?

Without resolving the issue of whether connectivity mitigation was even feasible, Solar Millennium brought up its proposal to move Mojave ground squirrels off the site at construction time, a clearance survey and relocation plan.

Leitner explained that this had been tried only once before, at the Boron mine expansion, and no follow-up studies were undertaken to see if it was successful. Only a narrow window exists when trapping would not do damage to lactating females and juveniles in the spring, and Leitner had reservations that moving squirrels was even worth doing.

Hacker said CESA obliges avoidance and minimization first, but thought it would be more beneficial to trap and salvage animals, not just plough them underground. This time monitoring would need to be done.

Leitner said translocated animals should be radiotransmittered, although the animals had a short lifespan -- 1 to 2 years. Discussion of possible fencing was brought up to prevent new animals from moving in during trapping efforts, but since the squirrels can climb and dig it would have to be expensive sheet metal dug two feet into the ground and four feet high. Hacker thought at least resident animals could be removed before grading and grubbing.

Dick Anderson said this was a difficult choice -- carrying out a plan that Leitner thought not worthwhile, or on the other hand, crushing a listed species. He said they needed a more formal translocation plan.

Mitigation

After various pubic comments for and against the project came in, Galati told the panel that if the In Lieu Fee Program could be used for Mojave ground squirrel mitigation, "we'd like to talk."

Ideas were bandied about for mitigation, such as retiring or buying out grazing allotments from BLM, more fencing, wildlife crossings on roads, regional raven management, funding Mojave ground squirrel radiotelemetry studies, and desert tortoise recovery plan actions.

Dick Anderson of CEC thought Solar Millennium could do a combination of tortoise and Mojave ground squirrel mitigation.

Michael Connor or Western Watersheds Project brought up the good point of how would fencing benefit the squirrels?

Dave Hacker also acknowledged that historically mitigation funds go to desert tortoise land acquisition, and typically if there are tortoise there will be Mojave ground squirrels (but not the other way around). But Mojave ground squirrels are not suppressed by ravens, so that would not mitigate. The threats to the squirrel are loss of habitat and degradation of habitat, and there is not a whole lot that can be done to increase populations besides removing grazing.

Dick Anderson still pointed out that all this does not mitigate for connectivity and the location. "You're trying to tease out mitigation on something you can't mitigate: connectivity. We keep beating around on this thing, the site."

Jarod Babula, counsel for CEC, said this was a must, in case the commission approved the project. We need to have mitigation, he explained, and do the best we can do.

Anderson stated that a 5:1 mitigation ratio for land acquisition for both the north and south fields would be needed for this high-value habitat, in addition to connectivity for desert tortoise and Mojave ground squirrel.

Solorio said he understood the frustration, so would 10:1 mitigation make it work?

Galati joined in, saying that they could use the In Lieu Fee Program or privately buy land in Mojave ground squirrel Core Areas, placing a conservation easement on them.

Elizabeth Klebaner of California Unions for Renewable Energy (CURE) said that the In Lieu Fee Program was not yet implemented, and that CEC must make a finding that mitigation would be effective.

Solorio stated that there was a lot of political will to make it happen, and he thought it would be available.

Dave Hacker seemed to agree with CURE, that there has to be an assurance that an area can be used for mitigation, and that people will not default on their purchase. He said DFG was asking people to put options on lands that would be available to DFG. But a lot of criteria could only be met at specific locations on the ground. He was not sure if the scheduling of he In Lieu Fee Program would work -- "seems tight to make this schedule."

Eric Solorio said he was not suggesting they write a check for connectivity.

Galati wanted the In Lieu Fee Program to mean "we fund; agencies pick the program or land." He wanted the government agencies to participate in a regional effort to find large blocks of land.

Hacker pointed out that SBX 34 did not change the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA) or CESA. There still must be a specific piece of land to mitigate.

"I see that," Galati agreed. Participation in the In Lieu Fee Program will not provide connectivity, he acknowledged. But he went on to say that trade-offs will have to be made. SBX 34 is an attempt to help. "No one will be completely happy."

Hacker ended explaining that connectivity is specific here, for the Little Dixie Wash Core Area -- the largest core area. It is not connectivity in general, but connectivity for this population. "It is not worth your time to look for enhancement measures that do not benefit this population."

The session ended without resolution, but resulted in merely a list of possible mitigation actions for both tortoise and the Mojave ground squirrel. The discussion highlighted the difficulty of fitting current findings from conservation biology into land management agendas, especially those with short deadlines.

^Good Mojave ground squirrel habitat in the southern project site, with Creosote, bursage, and winterfat.

^Late afternoon vista across the wide El Paso Wash north of Brown Road. Along the skyline will be Solar Millennium's large-scale parabolic trough solar thermal power plant if approved.

(See Dr. Leitner's article The Mysterious Mohave Ground Squirrel in Tortoise Tracks 19:2 Summer 1999)

HOME.....May 3 Workshop.....Ridgecrest Solar Power Project and Site.....Updates